Environmental racism & the climate crisis

by Paul Murphy

A major controversy broke out on the US left in the summer of 2020 when Professor Adolph Reed, a former Black civil rights activist, co-wrote a paper[1] warning against too much focus on racial disparity in the impact of Covid-19. His concern was “the extent to which particular inequalities that appear statistically as ‘racial’ disparities are in fact embedded in multiple social relations and how the dominant modes of approaching this topic impede the understanding of this larger picture.”[2] His critics, like Keeanga-Yamahatta Taylor, argued that in order to win White people “to an understanding of how their racism has fundamentally distorted the lives of Black people,”[3] it is necessary to point out racial disparities, not to downplay them with class reductionist arguments.

Article originally published in Issue 5 of Rupture, Ireland’s eco-socialist quarterly, buy the print issue:

The underlying facts were, however, uncontested. The coronavirus hit communities of colour in the US, in particular Black communities, at a grossly disproportionate rate. Black people got Covid at a higher rate than White people and died at a higher rate too. One statistic should suffice to drive the scale of this racial impact home - when age was accounted for, Black mortality from Covid-19 in the US was 3.57 times White mortality.[4] Indigenous people also suffered a mortality rate more than double that of White people.[5] This is not a ‘genetic’ phenomenon - it is a social one.

On a global level, the same process is clear. While majority-White countries are mostly nearing the end of full vaccination programmes, the majority of people in the Global South are not expected to be vaccinated until 2023.[6] With the private pharmaceutical companies holding onto their monopoly control, at the expense of hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths, Covid will continue to take the lives of people of colour, as well as mutate into new, potentially vaccine-resistant, variants.

Seen as an expression of the widening rift between humanity and nature[7], the racial impact of Covid-19 can help to shine a light on a much wider and repeated pattern of environmental crises targeting people of colour worldwide.

The Maldives, Image: ESA.

Climate change kills

While the extreme weather events of June 2021 in the US, Belgium, Germany, the UK, and China have forced a shift in the capitalist media reporting on climate change, their reporting over the last years would leave you with the impression that climate change represents a largely future problem. Headline after headline from even seemingly progressive media outlets like The Guardian talk about the ‘threat’ that climate change poses. But if a terrorist group was killing somewhere from 150,000 to 5,000,000 people a year in the western world, it is exceedingly unlikely that it would be presented as a future threat - it would be a problem for today. Yet, this is the sort of annual death toll exacted by climate change.[8] The vast majority of its victims are not White.

The World Health Organisation produced a useful, if somewhat outdated (the figures for today would be even more stark), map (see figure 1) which is striking. The countries with 0-2 climate change deaths per million a year are almost all majority White countries. Not one of the countries with more than 2 climate change deaths per million a year are majority White countries. All of the countries with more than 80 climate change deaths per million are countries with a majority Black population.

These maps, while highlighting one reality, obscure another - that within the ‘majority White’ countries, there are racial minorities which suffer disproportionately. Look at Australia, a ‘majority White’ country with an oppressed indigenous population. It appears yellow on the map, but Aboriginal people are dying at a high rate from heat stress[9] - often unable to afford appropriate air conditioning, and suffering from water shortages.[10]

It’s not just climate change either - all the effects of environmental destruction bear down much harder on communities of colour. In the US for example, Black children are twice as likely to develop asthma as their peers.[11] Together with Hispanic children, they are also far more likely to be admitted to the hospital for asthma (see figure 2).[12] This is directly related to the fact that Black Americans are almost twice as likely to live close to oil and gas facilities and the air pollutants they emit.[13]

As Nicole McCarthy argued in Issue 2 of Rupture[14], “[g]overnments the world over have been accused of environmental racism when it comes to disposing of this toxic waste, and rightly so. There tends to be a disproportionate amount of dumpsites near homes of people who are in marginalised groups and those earning a lower income.” She used the Environmental Protection Agency’s environment map to compare a sample of homes and their distance from waste facilities. Unsurprisingly, while most well-off areas had few waste facilities in their vicinity, whereas “for Traveller accommodation sites around Dublin, there are eight licensed waste facilities within one kilometre, 17 within two kilometres and 36 within three kilometres!” In Ireland, it is Travellers that bear the brunt of environmental racism.

Why?

Given that climate change and environmental crises do not have any agency to “choose” to target communities of colour, what is the reason for its blatantly racist consequences? The answer to this reveals a deeper truth about the nature of capitalism. In Malcolm X’s words, “you can’t have capitalism without racism”[15]. The economic system that we have, is not simply one which is based on private production for profit, with racism as a purely incidental or accidental side-effect.

Rather, we exist in a ‘racial capitalism.’ The ‘actually existing capitalism’ that we have is one that has been intertwined with racism from its very beginning. As Cedric Robinson outlined in his pioneering, if flawed[16], Black Marxism[17], “[t]he development, organisation and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, and so too did social ideology. As a material force, then, it could be expected that racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism.”[18]

““In Ireland, it is Travellers that bear the brunt of environmental racism.””

From the first beginnings of capitalism in Europe in the fifteenth century came the consolidation of race as the primary “rationalization for the domination, exploitation, and/or extermination of non-’Europeans’.”[19] Thus, colonisation, imperialism and the slave trade were not secondary features of this new economic system - but were central constituent components of it.

This racial capitalism is the underlying reason why Covid-19 disproportionately affects people of colour, why they are many times more likely to die as a consequence of climate change than White people, and why they face the brunt of environmental pollution. In a nutshell, capitalism produces for-profit and the ‘externalities’ of environmental destruction which that production results in are placed on the shoulders of the working class and small farmers generally, and disproportionately on people of colour. This operates through numerous more proximate causes.

One has been mentioned already above - the locating of polluting industries in areas where racial minorities live. As with many of these factors, here two things intertwine: Firstly, the tendency to place dangerous industries in working-class and poor communities, where ethnic minorities everywhere make up a disproportionately large amount of the working class; Secondly, even accounting for the factor of income, communities of colour are still disproportionately targeted.

A 2003 US Commission on Civil Rights report concluded: “It appears, therefore, that minorities attract toxic storage and disposal facilities, but these facilities do not attract minorities.”[20] Communities of colour are literally targeted for pollution. Why? Because the risk of being caught polluting illegally is substantially less. Communities with little wealth and political influence are less likely to be able to develop the political pressure or take the court cases which may be necessary to hold the companies to account. Even if the companies are fined, Dorceta Taylor, author of Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility argues “[t]he fines tend to be lower in communities of colour, especially Black communities and poor communities,”[21]

‘Leafy suburbs’ or urban heat islands

Another way that this environmental racism, and class discrimination, operates is through urban planning (or the lack thereof) which means that working-class communities and communities of colour live in areas that are much more exposed to extreme heat. In Ireland, a day’s traveling around Dublin, Belfast, Cork or Limerick will confirm a basic pattern. Large Council housing estates tend to have very few old trees. The parks are invariably bare fields with a few football pitches. Compare that to the more affluent suburbs, where it’s not for nothing that the phrase ‘leafy suburbs’ is used to indicate areas of relative wealth. The result is that on a very hot day, the temperature is likely to be 1 or 2 degrees Celsius less in the leafy areas, than in the concrete housing estates.

Of course for now, in Ireland, that is more a question of discomfort and quality of life than the danger of widespread death from extreme heat. But when you think that the exact same pattern is present in most developed capitalist countries that do experience extreme heat, from France to the US, you can understand the problem.

In the US, ‘redlined’ areas (neighbourhoods with the lowest ranking of safety for loans) are 2.6°C warmer than non ‘redlined’ areas.[22] These ‘urban heat islands’ are invariably poor neighbourhoods and with high percentages of minority racial or ethnic groups. The consequence is that, for example, two-thirds of deaths in Oregon from the summer’s heatwave were people of colour.[23] Not only are these areas at higher risk of extreme heat, they are also at higher risk of flooding!

Imperialism

A deeper reason connecting racial capitalism to environmental racism today is the legacy and continuation of imperialism. In a disgusting irony, recent research suggests that the first observable human impact on our climate may have been a genocide which reduced worldwide temperatures potentially causing what is known as the ‘Little Ice Age’.[24] As a result of the ‘Great Dying’, where 90% of the indigenous population of America was killed by European colonisers and the diseases they brought with them over the course of one hundred years, the amount of land cultivated in America was dramatically reduced and more carbon was drawn down from the atmosphere.

Colonisation was about the appropriation of nature and labour on an immense scale. What went hand in hand with this was a deep racism, casting those who were to be enslaved as ‘primitives’ or ‘savages’ who were less than human. As temperatures now rise dangerously, the uneven development of capitalism on a global scale has left people in the colonial and neo-colonial world extremely vulnerable to extreme weather events caused by climate change. As Walter Rodney writes in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa:

“A further revelation of growth without development under colonialism was the overdependence on one or two exports. The term “monoculture” is used to describe those colonial economies which were centered around a single crop. Liberia (in the agricultural sector) was a monoculture dependent on rubber, Gold Coast on cocoa, Dahomey and southeast Nigeria on palm produce, Sudan on cotton, Tanganyika on sisal, and Uganda on cotton. In Senegal and Gambia, groundnuts accounted for 85 to 90 percent of money earnings. In effect, two African colonies were told to grow nothing but peanuts!”[25]

““Colonisation was about the appropriation of nature and labour on an immense scale.””

The basic approach to the colonies and neo-colonies has been to leave them relatively undeveloped, as sources of raw materials and cheap labour. People familiar with the story of the Irish famine, where food exports continued while the potato crop failed, will understand how this model of resource extraction leaves these societies far more vulnerable to crop failure as a consequence of climate change. It also means that in the main the people in the regions of the world most affected by extreme heat are unable to afford the air conditioning which would make it bearable (while also contributing to it worsening in the long run.)[26]

Madagascar, an island nation off the east coast of Africa, is currently facing a famine with over one million people food insecure. Time magazine has described it as the first famine “in modern history to be solely caused by global warming.”[27] While it makes for an arresting headline, it fails to capture the responsibility of imperialism for an economy where vanilla accounts for 20% of exports[28] and millions of people are dependent on a good food crop in any given year in order to survive.

Climate colonialism

The same tendency to target people of colour with polluting industries in the developed capitalist nation operates on a global scale too. Forty-six per cent of Europe’s separated plastic waste is exported from its country of origin mostly to Asian countries.[29] A huge percentage of waste from western, and mostly White, countries, exported eastwards. In Indonesia[30], for example, the plastic waste from Europe ends up being burned as cheap fuel by businesses, releasing toxins into the air, polluting the water and poisoning the food supply. The consequence is that some eggs, for example, contain levels of dioxins that are 70 times more than what the European Food Safety Authority recommends for a safe daily intake![31]

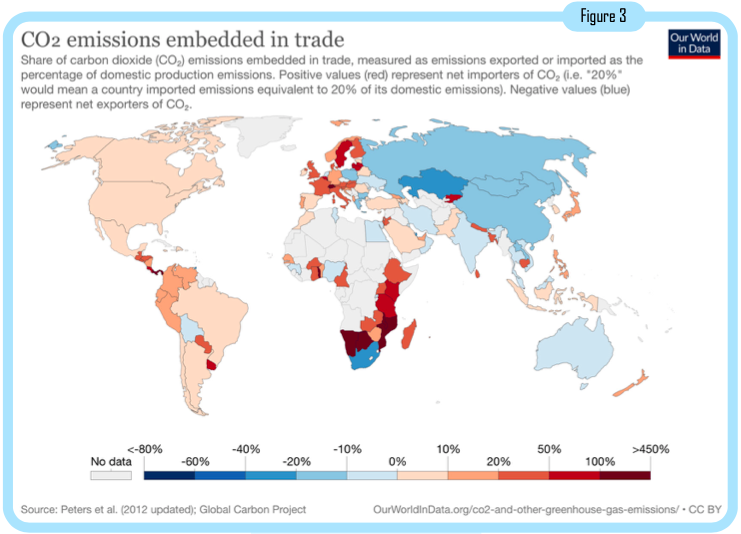

Increasingly, CO2 emissions are effectively exported too. The western world partially reduces its domestic emissions by shifting production eastward (as illustrated in figure 3). A reduction in emissions in western Europe may help governments and corporations greenwash themselves, but if the total emissions remain the same, the climate doesn’t care. Together with some of these exported CO2 emissions will be exported air pollutants.

It is not only the actual pollution which destroys the lives and communities in the Global South, but ironically also the ‘market mechanism’ of carbon offsets promoted by the European Union and various capitalist governments.

The Oakland Institute debunks[32] the suggestion that carbon trading is a ‘win-win’ for the environment and rural communities. Instead by looking at the actions of Green Resources, a mostly Norwegian owned company which styles itself as “[t]he leading sustainable forestry company in Africa”,[33] they show how villagers in Uganda have been forcibly evicted, have had their access to land and food restricted, as well as lost their incomes as a consequence of Green Resources actions. The result is that greenwashing capitalist processes formally aimed at reducing emissions actually serve to make life even harder for those suffering most from the effects of climate change. They conclude that “there is mounting evidence that these corporate land acquisitions for climate change mitigation—including forestry plantations—severely compromise not only local ecologies but also the livelihoods of some of the world’s most vulnerable people living at subsistence level in rural areas in developing countries.”[34]

Revolutionary subjects

The determination of the western media to present the environmental movement as a paternalistic movement of concerned White saviours reached arguably its nadir with the literal airbrushing of a young Black woman from a picture of climate activists.[35] Twenty-three-year-old Ugandan activist, Vanessa Nakate, the founder of climate action groups Youth for Future Africa and the Rise Up Movement, was simply disappeared to allow the Associated Press to focus on the White faces of Greta Thunberg and three other young White women.

Far from the ‘White saviour’ image of the environmental movement, it is people of colour and indigenous people who are on the frontline of the struggle against climate change and environmental destruction, and often women (see Women and Nature, Rupture Issue 3). From the Dakota Access Pipeline and Keystone XL to the current movement to Stop Line 3 - a proposed pipeline from Alberta in Canada to northwest Wisconsin in the US - it is indigenous people who have faced police violence in North America in their fight to stop fossil fuel infrastructure. Its impact would be to destroy nature that indigenous people have relied on for centuries for food and water, and that, whether people realise it or not, we all rely on. In Latin America and Africa, the struggles against mining, invariably organised by indigenous and local communities, are innumerous. These activists don’t just face police violence, they are all too often murdered. Global Witness reports a record 212 activists were murdered in 2019, an increase of 30% from 2018 and more than four ‘defenders’ a week.[36]

“For the earth to live, capitalism must die”

The image of the environmental movement as a White, middle class and western phenomenon could hardly be further from the truth. The frontline of the environmental struggle is in the Global South and the leaders are people of colour.

Indigenous people not only lead the struggles against the consequences of climate change, their communities also offer an important glimpse of how the rift between humanity and nature could be healed. Indeed, part of the racist denigration of the colonised by western imperialism was precisely because they had a much healthier relationship with nature. As Jason Hickel outlines:

“In the writings of European colonisers and missionaries we see they were dismayed that so many of the people they encountered insisted on seeing the world as alive – seeing mountains, rivers, animals, plants, and even the land as filled with agency and spirit. Europe’s elites saw animist thought as an obstacle to capitalism – in the colonies just as in Europe itself – and sought to eradicate it. In order to do so, they set up a new binary: ‘civilised’ versus ‘savage’. To become civilised, to become fully human, and to become willing participants in the capitalist world economy, Indigenous people would have to be forced to abandon animist principles, and made to see nature as an object.”[38]

The resolution (see box) adopted by the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth in Cochabamba, Bolivia (the site of the successful ‘water war’ against privatisation in the early 2000s) in April 2010 illustrates the radical ideas which are an enormous contribution to an ecosocialism today.

As Michael Löwy argues, while “[o]ne can criticize the mystical and confused aspect of the concept of “Mother Earth” (Pachamama in the Indigenous languages Aymara and Quechua), as some leftist Latin American intellectuals have done, or point out the impossibility of giving an effective legal expression to the “rights of Mother Earth,” as jurists have done. Yet this would be to lose sight of the essential point: the powerful, radically anti-systemic social dynamic that has crystallized around these slogans.”[39] This example is already inspiring activists to pass similar “rights of nature” motions, as People Before Profit Councillor Maeve O’Neill has done in Derry.

While ecosocialists don’t seek a utopian return to a pre-industrial world, just as Marx and Engels saw the ‘primitive communist’ societies containing a germ of the future communist society, another seed is present within indigenous cultures. That is a healthy relationship with, and respect for, nature and the notion of the “good life” being a qualitative, rather than a quantitative one. These are concepts that would be restored at a higher level of development in an ecosocialist society.

Resolution agreed by World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth

(Cochabamba, Bolivia, April 2010)The capitalist system has imposed on us a logic of competition, progress and limitless growth. This regime of production and consumption seeks profit without limits, separating human beings from nature and imposing a logic of domination upon nature, transforming everything into commodities: water, earth, the human genome, ancestral cultures, biodiversity, justice, ethics, the rights of peoples, and life itself.

Under capitalism, Mother Earth is converted into a source of raw materials, and human beings into consumers and a means of production, into people that are seen as valuable only for what they own, and not for what they are.

Capitalism requires a powerful military industry for its processes of accumulation and imposition of control over territories and natural resources, suppressing the resistance of the peoples. It is an imperialist system of colonization of the planet.

Humanity confronts a great dilemma: to continue on the path of capitalism, depredation, and death, or to choose the path of harmony with nature and respect for life.

It is imperative that we forge a new system that restores harmony with nature and among human beings. And in order for there to be balance with nature, there must first be equity among human beings.

We propose to the peoples of the world the recovery, revalorization, and strengthening of the knowledge, wisdom, and ancestral practices of Indigenous Peoples, which are affirmed in the thought and practices of “Living Well,” recognizing Mother Earth as a living being with which we have an indivisible, interdependent, complementary and spiritual relationship.”[40]

Notes

1. Merlin Chowkwanyun, Ph.D., M.P.H., and Adolph L. Reed, Jr., Ph.D., ‘Racial Health Disparities and Covid-19 — Caution and Context’, 16 July 2020.

2. Adolph Reed, Jr and Merlin Chowkanyunp,. ‘Race, Class, Crisis: The discourse of racial disparity and its analytical content’, Socialist Register 2012, p. 151.

3. Quoted in ‘A Black Marxist Scholar Wanted to Talk About Race. It Ignited a Fury’, New York Times, 14 August 2020.

4. Graeme Wood, ‘What’s Behind the COVID-19 Racial Disparity?’, The Atlantic, 27 May 2020.

5. ‘Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity’, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 16 April 2021.

6. More than 85 poor countries will not have widespread access to coronavirus vaccines before 2023.

7. See the writings of Rod Wallace, e.g. ‘Dead Epidemiologists: On the Origins of COVID-19’ (Monthly Review, September 2020) and Mike Davis, The Monster Enters: COVID-19, Avian Flu and the Plagues of Capitalism Paperback, (OR Books, 2 July 2020)

8. Estimating deaths from climate change is understandably an imprecise science. The most conservative estimates of the WHO put it at 150,000 annually (https://www.who.int/heli/risks/climate/climatechange/en/), while others put it as high as 5 million (https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/news/20210708/climate-change-already-causes-5-million-extra-deaths-per-year).

9. Gideon Polya, ‘Australian climate criminality, heat stress deaths & Australian Aboriginal Ethnocide’, Countercurrents, 19 December 2019.

10. ‘Too hot for humans? First Nations people fear becoming Australia's first climate refugees’, The Guardian website 17 December 2019.

11. ‘America's dirty divide: how environmental racism leaves the vulnerable behind’, The Guardian website 11 February 2021.

12. Graphic from ‘America's dirty divide: how environmental racism leaves the vulnerable behind’, The Guardian website 11 February 2021.

13. Ibid

14. Nicole McCarthy, ‘Down In The Dumps’, Rupture Issue 2 (Winter 2020).

15. Speech Malcolm X gave to the ‘Militant Labor Forum’ 29 May 1964 available on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ux_zQnD0WfY&t=1846s

16. For an insightful recent critique, see Ken Olende, ‘Cedric Robinson, racial capitalism and the return of black radicalism’ International Socialism Journal Issue 169 and for an older critique, see Cornel West, ‘Review of Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition by Cedric J. Robinson’ Monthly Review Vol. 40, No. 4: September 1988.

17. Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, (University of North Carolina Press, 1983 republished 2000).

18. Ibid, p. 2.

19. Ibid, p. 27.

20. Chapter 2, ‘Not in My Backyard: Executive Order 12,898 and Title VI as Tools for Achieving Environmental Justice’, US Commission on Civil Rights, October 2003.

21. Ivana Ramirez, ‘10 Examples of Environmental Racism and How it Works’, Yes Magazine, 22 April 2021.

22. Alexandre Witze, ‘Racism is magnifying the deadly impact of rising city heat’, Nature 14 July 2021.

23. Rachel Ramirez, ‘Climate change is fueling mass-casualty heat waves. Here's why experts say we don't view them as crises’, CNN edition website, 13 July 2021.

24. Jonathan Amos, ‘America colonisation ‘cooled Earth's climate’’, BBC News website, 31 January 2019.

25. Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, (Howard University Press, 1981), p. 234.

26. A heatwave in northern India where the lack of air conditioning exacerbates a mass casualty heatwave is the premise of the fictional work by Kim Stanley Robinson, Ministry of the Future, (Orbit Books, 2020).

27. Aryn Baker, ‘Climate, Not Conflict. Madagascar's Famine is the First in Modern History to be Solely Caused by Global Warming’, Time magazine, 20 July 2021.

28. OECD Country Profile for Madagascar (https://oec.world/en/profile/country/mdg)

29. George Bishop, David Styles, Piet N.L. Lens, ‘Recycling of European plastic is a pathway for plastic debris in the ocean’ Environment International, Vol 142, 2020.

30. Johnny Ford, ‘Plastic waste from Western countries is poisoning Indonesia’, World Economic Forum website, 4 December 2019.

31. Ibid

32. ‘The Darker Side of Green: Plantation Forestry and Carbon Violence in Uganda’, The Oakland Institute, November 2014

33. Green Resources website https://greenresources.no/

34. ‘The Darker Side of Green: Plantation Forestry and Carbon Violence in Uganda’, The Oakland Institute, November 2014

35. Kenya Evelyn, 'Like I wasn't there': climate activist Vanessa Nakate on being erased from a movement’, The Guardian, 29 January 2020

36. Patrick Greenfield and Jonathan Watts, ‘Record 212 land and environment activists killed last year’, The Guardian, 29 July 2020

37. Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance, (Verso, 2019).

38. Ch. 1, Jason Hickel, Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, (Random House, 2020).

39. Ch. 5, Micahel Löwy, Eco-Socialism: A Radical Alternative to Capitalist Catastrophe, (Haymarket Books, 2015)

40. Extracts reproduced at Ch. 5, Löwy, ibid.