The Work is Mysterious and Important

by Patrick Flynn

The idea that the modern workplace requires us to adopt a new persona separate to our own identity isn’t a new one. As prominent an authority as the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre complained in 1981 that ‘modernity partitions each human life into a variety of segments, each with its own norms and modes of behaviour. So work is divided from leisure, private life from public, the corporate from the personal… and all these separations have been achieved so that it is the distinctiveness of each and not the unity of the life of the individual who passes through those parts in terms of which we are thought to think and how to feel’.[1] While MacIntyre, who recently died, had long left his Trotskyist roots in Britain’s International Socialists behind when he wrote these words, he remained an often withering critic of capitalist modernity, and many office workers will identify with his analysis here.

“Science fiction, as shows like Black Mirror remind us, is unfortunately often better at paralleling our present problems than making optimistic predictions of the future. ”

Severance, the second season of which debuted earlier this year on Apple TV - ironically delayed after the Actors’ and Writers’ Strikes in 2023, as the show’s creators resisted the wider attacks on conditions in the film and TV industries perpetrated by corporations like Apple - takes the developments observed by MacIntyre, and the wider absurdities of modern office culture, to their dystopian sci-fi conclusion. Science fiction, as shows like Black Mirror remind us, is unfortunately often better at paralleling our present problems than making optimistic predictions of the future. Of the various predictions of nineties Star Trek, that most optimistic of sci-fi franchises, made about life in the mid-2020s, we didn't get the unification of Ireland or the Neo-Trotskyist government in France, but we did get the dystopian repression of California protests.[2] Likewise, Severance holds a mirror up to our dysfunctional workplaces: the anhedonia instilled by repetitive work and lack of autonomy in work, echoing Marx’s concept of alienation of labour; the cringeworthy HR attempts at corporate wellness; the petty narcissism of small differences which exists between different, internally squabbling, sections of the office; and managers who expect overburdened workers in chronically understaffed workplaces to seemingly perform miracles.

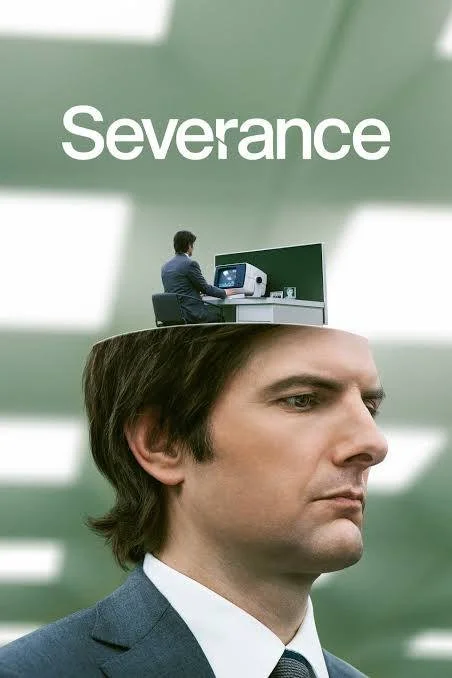

The show focuses on four workers who have agreed to undergo ‘severance’, the eponymous procedure where workers forget everything about work when they leave the office, while they forget everything outside when they enter. The process effectively partitions workers into two personalities: ‘innies’, who are only conscious while working, and ‘outies’, who are only conscious outside of work. Innies are essentially slaves whose life is wholly devoted to work and have no possibility of ever leaving the office, while outies, in their various ways, are also tied to the Severance dichotomy by their own trapped positions in the world outside. The show follows the innies, led by Mark S, (Adam Scott) as they lead a revolt within the office against their imprisonment, while the outies both oppose and aid the innies in their struggle, as Severance gradually starts showing cracks.

“Lumon is portrayed as a vast corporation with a bewildering number of internal departments that struggle to understand the meaning of their own work and regard other departments with suspicion, certainly something that many office workers will identify with. ”

The Severance procedure is the brainchild of Lumon Industries, a nefarious company founded in the nineteenth century by Kier Eagan. Kier is a messianic figure and the progenitor of Lumon’s dynastic ownership, with heavy shades of L. Ron Hubbard, Joseph Smith and Henry Ford. The company inculcates a cultish, quasi-religious devotion towards him amongst its employees, who are forced to learn his tedious, Dianectics-like Compliance Handbook by heart. Lumon is portrayed as a vast corporation with a bewildering number of internal departments that struggle to understand the meaning of their own work and regard other departments with suspicion, certainly something that many office workers will identify with. Dominating the economic life of the town where Mark and the other characters in the show live, it is gradually revealed as having devastated previous towns where it closed its plants, leaving them empty, barren shells - a nod to any number of towns in the American rust belt. It regularly declares its care for its employees, organising bizarre - and extremely camp - spontaneous perk events like ‘egg-bar socials’ and ‘music-dance experiences’ for the innies. After they initially begin to challenge the system, it even declares that ‘Lumon is learning’ and begins offering them facile concessions - while tirelessly ensuring the Severance procedure remains untouched.

“The Lumon office areas where the innies work are particularly memorable, with their brightly lit but bare and spartan white office walls emphasising the soulless oppressiveness of Lumon. ”

Severance, along with Tony Gilroy’s recently concluded Star Wars series, Andor, is one of the most impressive sci-fi shows on television today - aside from the obvious parallels in their intelligent, politically aware writing, it’s probably not a coincidence both were released gradually rather than all at once, allowing them to make a greater impact in driving conversation. Severance is certainly well-written, tying together camp surrealism, pathos, and compelling sci-fi themes very well. It is also excellently shot with fantastic cinematography and set design. The Lumon office areas where the innies work are particularly memorable, with their brightly lit but bare and spartan white office walls emphasising the soulless oppressiveness of Lumon. It’s not surprising that Jacques Tati, one of my favourite filmmakers, has been cited by the creators as a major influence on the show; Tati’s famous 1967 film, Playtime, notably featured his iconic proto-Mr Bean character, Monsieur Hulot, getting lost in a labyrinthine, anodyne office building, which Tati contrasts to the beautiful, old Paris outside. The cast is also great, featuring both emerging talents like Britt Lower, Zack Cherry and Travell Tillman, and veteran actors like John Turturro, Christopher Walken and Patricia Arquette. Notably, Turturro and Walken’s characters are one of the vanishingly few well-written examples of a romance between older gay men being portrayed on television, or wider popular culture for that matter.

While the plot is compelling, I felt that it somewhat lost its way at the end of the second season, as some interesting plot threads fell by the wayside. It was disappointing that other interesting characters in the show like Ricken (Michael Chernus), outie Mark’s self-help book-writing brother-in-law whose books serve as an interesting foil to the cult of Keir, didn’t get much airtime at the end of season two. Nonetheless I am looking forward to the third season, reportedly the last, which hopefully will end the show strongly and give the more interesting plot threads more airtime. Severance stands out, alongside Calvin Kasulke’s 2021 novel Several People are Typing - the darkly funny Covid-era story of an office worker getting trapped inside a Slack chat - as one of the more appropriately bizarre skewerings of office culture in recent times, a suitably amusing and cathartic watch for those of us decompressing at home after a long, tiring day in the office.

Notes

1. Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (1981), pp. 204-205.

2. As depicted in The Next Generation episode ‘The High Ground’ and the Deep Space Nine two-parter ‘Past Tense’. https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/The_High_Ground_(episode); https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Past_Tense,_Part_I_(episode)