Plan to Fail-The Government’s Climate Action Plan

By Des Hennelly

Article originally published in Issue 7 of Rupture. You can buy the print issue here:

Down the barrel of a gun

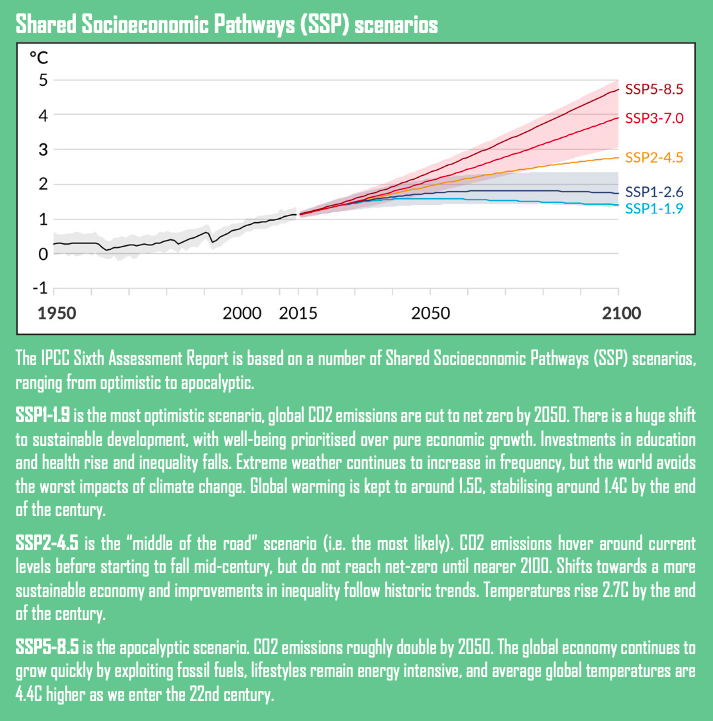

The Government’s Climate Action Plan was published in November 2021 in the shadow of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report on the science of climate change that was released three months earlier. The IPCC report laid out in shocking detail the perilous state of our climate and the accelerating pace of climate change. The potential scenarios highlighted ranged from dangerous to what the IPCC referred to as ‘apocalyptic’. The IPCC scenario ranked ‘most likely’ has temperatures reaching a catastrophic 2.7C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. But the IPCC also warns of its ‘apocalyptic’ scenario, in which emissions double by 2050 as the global economy continues to grow rapidly, driven by fossil fuels. This scenario results in global temperatures at a civilisation-ending 4.4C above pre-industrial levels.[1]

The frightening reality is that the resource competition and exponential capital growth dynamics of capitalism, alongside the self-interest of economic and political elites, are driving a rapidly escalating risk of the IPCC’s worst-case scenarios being fulfilled. The intensifying conflict between the Western and Russian empires, now centred on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has added a new momentum towards apocalypse in the coming decades.

It is against this bleak and rapidly darkening backdrop that we assess the 2021 Climate Action Plan.

The commitments

The plan’s opening chapters provide an analysis of Ireland’s emissions record. It highlights that the top three sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Ireland in 2020 were agriculture at 37.1%, transport at 17.9% and energy at 15%. It also notes that despite the severe Covid-19 restrictions in 2020, greenhouse gas emissions in Ireland decreased by only 3.6% compared to 2019. Notably, emissions increased in 2020 in the agriculture sector, arising from an increase in nitrogen fertiliser use and liming, and higher dairy cattle numbers and milk production.

““The IPCC also warns of its ‘apocalyptic’ scenario, in which emissions double by 2050 as the global economy continues to grow rapidly, driven by fossil fuels””

The Climate Action Plan commits Ireland to net-zero emissions by 2050, and a cut of 51% by 2030 compared to 2018 levels. First up, it should be noted that this is even less ambitious than the EU’s own underwhelming European Green Deal, which targets cuts of 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. If 1990 was used as the starting point, the emissions reduction targets set out in the Climate Action Plan would provide for just 45% of a reduction between 1990 and 2030.

A further major weakness of the plan is that the target reductions are stated in ranges by sector - energy, industry, built environment, transport and agriculture. For example, the planned emission reductions for the transport sector are stated in a range of 42% to 50%, and the target for the industry sector is in the range of 29% to 41%. The overall plan -51% target by 2030 requires that the top of the target ranges are reached in all of the sectors. In fact, as Eamon Ryan was forced to admit at the launch of the plan, even if the top-end reductions are achieved in all categories, the plan still only gets to -48% reductions, with the balance to -51% to come from unspecified measures in unspecified sectors.

At the other end of the emissions reductions targets by sector, the sum of the bottom-end reductions only gets to -37% by 2030. So even a first reading of the plan reduces one’s confidence that the -51% target will be reached.

Core measures & further measures

As we read through the plan, it becomes evident that closing the gaps between the bottom and top end of the ranges is heavily dependent on processes and technologies that are unproven, uncosted, and/or not currently scaleable.

In Chapter 4, we find that the emissions reduction measures are split into (i) Core Measures and (ii) Further Measures. The plan defines Core Measures as those that “cover the established fundamentals of decarbonisation, such as developing renewable power for electricity supply, electrification across demand sectors, and demand management measures”. But the report states that these Core Measures are not sufficient to achieve the Climate Action Plan targets.

The report states that ‘Further Measures’ will be necessary to reach the -51% emissions cut target. These Further Measures are described as “more technically challenging, or are not yet available at scale in Ireland”. The report states that their potential impact and cost will evolve over the coming decade, and work will be undertaken to refine the potential of these measures and to set relevant targets for inclusion in future Climate Action Plans.

““A large proportion of the planned reductions are tagged to these unproven and undeveloped Further Measures””

Examples are given of the type of Further Measures that are envisaged, such as “biogas/biomethane with currently limited supply; green hydrogen, where electrolysis technologies are still being developed and costs are relatively high; and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) which requires capital expenditure and the development of transport and storage infrastructure”. These are at best unproven, highly speculative, and some are likely to be a dangerous distraction from efforts to reduce emissions. Yet a large proportion of the planned reductions are tagged to these unproven and undeveloped Further Measures.

The plan in the Further Measures data provided per sector is unclear and inconsistent, but it appears that planned reductions tagged to unproven and speculative Further Measures are a quarter to a third of the total planned reductions by 2030. This roughly equates to the gap, highlighted above, between -51%, being the sum of the top end of the sector target ranges, plus a bit more, and -37%, being the sum of the bottom end of the ranges.

So we can see that the -51% target itself falls far short of what we need to deal with the scale and speed of the threat we face, and relies heavily on reaching the top end of all the sector target ranges, which are themselves very heavily dependent on unproven Further Measures. The further we dig, the weaker the plan looks.

Post-Climate Action Plan Carbon Budgets

Subsequent to publication of the Climate Action Plan, draft carbon budgets have been approved by the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Environment for the 2021 to 2025 and 2026 to 2030 periods. But here more weaknesses and slippage quickly emerge.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, annual emission reductions need to be 7.6% on average across the planet to have a 66% chance of staying below a 1.5C global temperature increase.[2] But in fact, much of the most recent science suggests much more needs to be done to ensure we don’t exceed 1.5 degrees warming - itself a death sentence for large parts of humanity and life on the planet.

It should also be noted that developed countries need to make cuts greater than 7.6% per annum to offset the need for lower reductions in many countries in the Global South. These countries need to provide for populations impoverished by extraction and exploitation by corporations overwhelmingly based in the Western developed world. But despite this urgent need for cuts in Ireland of greater than 7.6% per annum, the Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil, and Green Party Programme for Government committed to average reductions in Ireland of just 7% per annum.

However, the recently approved carbon budgets are much lower again, equivalent to average annual reductions of just 5.7% per annum to 2030. But it gets worse; much of that grossly insufficient average annual reduction is back-loaded, with cuts of just 4.8 % per year for the 2021 to 2025 period, followed by cuts of 8.3% per year for the second five-year budget.[3]

Each layer of the analysis we conduct reveals more gaps and weaknesses, and already there has been slippage against the targets in the 2021 to 2025 carbon budget. New data compiled by the MaREI Research Centre for Energy, Climate and Marine at UCC, indicates that Ireland’s carbon emissions fell in 2021 by between 1.8% and 3.7% below 2018 levels, instead of the target reduction of 4.8%.[4] This comes despite significant periods of lockdown and restrictions during 2021. It is also likely that emissions will increase in 2022.[5]

Professor Barry McMullin of Dublin City University has also recently highlighted that the budgets take no account of emissions from aviation and shipping. Professor McMullin told an Oireachtas Committee in January that “These are significant for Ireland… primarily in aviation.” He added, “It therefore falls to this Committee to make such provision. Again, this indicates that the proposed budgets should be reduced, at least by the projected national share of such international aviation and shipping emissions. A minimum estimate of this would be 40 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent over the period 2021-2030.”[6] But the 2021 Climate Action Plan and the subsequent Carbon Budgets make no allowance for marine and aviation emissions whatsoever.

Transport - bad measures

The transport section of the Climate Action Plan is worth specific attention for the troubling nature of the proposed actions. The plan notes that the transport sector has been the fastest-growing source of emissions in Ireland, showing a 100 percent increase between 1990 and 2020, due to a massive increase in vehicles on the road. It states that transport currently accounts for approximately 20% of Ireland’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with road transport responsible for 96% of this.

A fundamental flaw in this important section of the plan is that it targets 70% of the planned reduction in transport emissions to come from switching from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to electric vehicles (EV). The plan seeks to increase the national fleet of EVs and low emitting vehicles (LEVs) on the road to 945,000, made up of 845,000 electric passenger cars, 95,000 electric vans, 3,500 low emitting trucks, and 1,500 electric buses.

““The transport sector has been the fastest-growing source of emissions in Ireland, showing a 100 percent increase between 1990 and 2020.””

This switch to EVs represents a huge challenge that generates other major problems of extraction and sustainability. The International Energy Agency analysed the global outlook for demand arising from a switch to clean energy and the effect it will have on demand for minerals and stated “A concerted effort to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement (climate stabilisation at “well below 2°C global temperature rise”, as in the SDS) would mean a quadrupling of mineral requirements for clean energy technologies by 2040. An even faster transition, to hit net-zero globally by 2050, would require six times more mineral inputs in 2040 than today.”[7]

A switch to EVs of the magnitude envisaged in the Climate Action Plan would drive humanity to approach and exceed other planetary boundaries and intensify other aspects of our environmental crisis.

A truly sustainable climate action plan would instead have free, frequent, and fast public transport as a central pillar. An alternative transport strategy based on greatly expanding public transport capacity and geographical reach, and making it free at the point of use, represents a far more sustainable transport approach that reduces emissions and avoids the extremely damaging extractive impacts of a switch to EV cars.

The Government’s recent announcement of a 20% reduction in public transport fares is estimated to cost the Exchequer €54m for nine months.[8] This indicates that the full abolition of charges for public transport would cost about €360m per annum. This is a modest cost for a policy that would have a large beneficial impact on the cost of living for low and middle-income people, would sharply reduce carbon emissions, and greatly improve urban air quality.

The built environment & retro-fitting - half measures

The recently announced national retrofitting scheme flows from the 2021 Climate Action Plan. But despite the very poor energy performance of homes in Ireland, the plan’s target for 500,000 homes to be retrofitted by 2030, and associated funding allocations, are the same as Fine Gael’s 2019 Climate Action Plan. Even if the plan’s targets are reached, only half of the building energy rating problem will have been addressed.

According to the plan, 11.2% of emissions in 2018 were in residential settings. It also highlights that residential CO2 emissions per person in Ireland are 60% higher than the EU average and more than three times as high as in Denmark and Finland. Our national building stock is 70% reliant on fossil fuels. Half of Irish housing stock, approximately one million homes, has a Building Energy Rating (BER) of D1 or worse, and only 10% is B2 or better.

The retrofitting scheme will be funded by the carbon tax, which is paid mainly by low and middle income people. But it is largely higher earners and wealthy people that will be able to afford 50% of the cost of a full deep retrofit, approximately €25,000. The scheme will therefore be largely economically regressive, effectively transferring wealth from low and middle-income people to high earners and the wealthy.

Agriculture - unknown measures

Agriculture accounts for over a third of Ireland’s emissions, yet its Climate Action Plan percentage reduction targets are the lowest of any sector, in a range of 22% to 30%. Within that, only a small part of the planned agriculture emissions reductions are tagged to the relatively reliable Core Measures, with most of the planned reductions tagged to nebulous and undefined Further Measures. The fact that the Irish Government signed up to a global pledge to limit methane emissions by 30% by 2030 at COP26, but then followed swiftly with another statement that Ireland itself would only commit to a 10% cut in methane[9] is another perverse demonstration of the unforgivable lack of seriousness that emerges at every stage.

Tracking towards apocalypse

The Climate Action Plan aims for a -51% cut in emissions by 2030, a target that is far short of what is needed to avoid catastrophic climate change. But even on its own terms, it is shot through with gaps, speculative measures, and backloading that creates a high probability that even the hopelessly insufficient target of -51% by 2030 will not be met.

Against the backdrop of a plan destined to fail, we watch as data centres proliferate across the country, consuming a rapidly growing volume of fossil-fuel generated electricity, as well as much of the increases in wind generated electricity that are badly needed to replace fossil fuel generation elsewhere.

The 2021 Climate Action Plan is a failure of vision, ambition, and planning. It is a recipe for tracking the IPCC’s ‘apocalyptic’ scenario. Ecosocialists will have to move speedily to replace it.

Notes

1. IPCC, ‘Climate Science 2021 - The Physical Science Basis Summary for Policymakers’, August 2021 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf.

2. UNEP, ‘Cut global emissions by 7.6 percent every year for next decade to meet 1.5°C Paris target - UN report’, 29 November 2019 https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/cut-global-emissions-76-percent-every-year-next-decade-meet-15degc.

3. An Taisce, ‘Proposed Carbon Budgets Not Consistent with Paris Agreement Obligations’, 8 February 2022 https://www.antaisce.org/news/proposed-carbon-budgets-not-consistent-with-paris-agreement-obligations.

4. Oonagh Smyth, ‘Ireland missed emissions targets in 2021 - early data’ RTE, 14 April 2022.

5. Colm O’Sullivan, ‘Ireland's carbon emissions will continue to rise, says expert’, RTE, 20 February 2022.

6. Oireachtas Joint Committee on Environment and Climate Action, ‘Report on the proposed Carbon Budgets’, February 2022 https://data.oireachtas.ie/ie/oireachtas/committee/dail/33/joint_committee_on_environment_and_climate_action/reports/2022/2022-02-07_report-on-the-proposed-carbon-budgets_en.pdf.

7. IEA, ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions’, March 2022 https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary.

8. The Journal.ie, ‘Cost of living package: Public transport fares to be cut by 20% and electricity customers to get €200 credit’ 10 February 2022 https://www.thejournal.ie/cost-of-living-5679921-Feb2022/.

9. Pat Leahy, Harry McGee, Denis Staunton, ‘Cabinet's climate action plan to bypass Cop26 summit pledge on reducing methane’, Irish Times, 3 November 2021.