Social Reproduction Theory and Women in Society

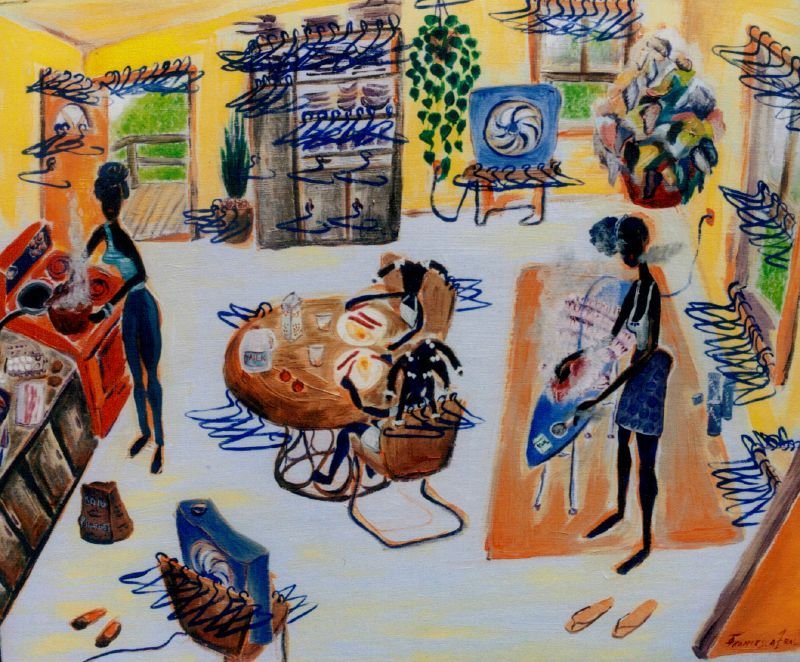

by Emma Finnamore

Social Reproduction Theory describes how capitalism is not only an economic system, but a system around which we organise every aspect of life, including recreation, leisure, social institutions, and even interpersonal relationships. It is an expansion on traditional Marxist theory. Where labour is the productive work developing capital for the market, reproductive labour is the familial and communitarian work that goes into sustaining and reproducing the worker.[1] Social Reproduction Theory (or SRT hereafter) evaluates not only an individual’s relationship with labour, but also their relationship with others and their community. No one lives or dies alone in this world. Does a working person have a home, a bed to sleep in, groceries in the fridge, someone to cook them breakfast? If they break their arm is there someone to bandage it? Do they have access to clean water, green spaces, or mental health services? We as individuals are only able to sustain ourselves through the conscious actions of the carers and reproductive labour forces that surround us.

Understanding SRT

A key aspect of modern SRT is a gendered analysis of the economy. Many caring services are in the realm of domestic labour and subsequently delegated to women. Never-ending tasks such as cleaning, cooking, and childrearing have historically fallen upon wives, mothers, and women in general, their labour power both indispensable and unpaid. Women also quite literally reproduce the workforce through childbirth. SRT reveals their ‘invisible’ work, bringing to light the intertwined rights of women and workers.[2]

Article originally published in Issue 7 of Rupture. You can buy the print issue here:

In the early 20th century Lenin wrote about the status of women as ‘domestic slaves’, and a legacy of this is still visible today around the globe.[3] Through the expectation of domestic labour as the duty and responsibility of a ‘wife’, the capitalist system arranges a woman’s dependence on men as the family breadwinner. In Women and Socialism, August Bebel, founder of the Socialist Democratic Party in Germany, asserted that the working population could never be liberated as long as women were oppressed and women would be oppressed as long as their wellbeing was directly determined by their husbands.[4] Today, when women pursue careers outside the home, they are burdened with an extended workday, returning home and still expected to contribute disproportionately to chores, childcare, household organisation, and so on. This is exacerbated by working from home. A report of the United Nations stated that before the pandemic, women contributed about three times more to caring and domestic tasks than men in the same household. Since then, due to closing schools and overburdened medical centres, the unpaid care has only increased and become more stressful. [5] As a result of the entanglement of the personal and the economic spheres of life, SRT emphasises a demand for equality and democracy in both.

Originally, ‘reproduction’ as outlined in the first volume of Marx’s Capital was used to denote the recreation of the entire capitalist society and social structure as a whole, related to the capital accumulation necessary to create profit and market growth.[6] SRT examines the excesses of this process outside the workplace, looking at the relations between the worker and the societal structure that prepares and regenerates this individual to be ready for work. While ‘social reproduction’ as a term has historically been used by capitalist philosophers and enlightenment thinkers, SRT developed through the work of revolutionary feminist activists and scholars.[7] Alongside the larger mainstream feminist movement in the 1970s, an interest in the recognition of housework as labour grew and sparked protests globally. The “Wages for Housework” Campaign, initiated by Silvia Federici and other Italian feminists, and the national ‘Women’s Day Off’ strike in Iceland, among others, raised awareness about the central role women play in socially reproductive labour. These groups demanded that domestic labour be recognised not only as hard work to be appreciated, but understood as an integral aspect of society without which the capitalist system could not continue. To forgo this analysis is to ignore half of the working population and dismiss the work it takes to ‘hold up half the sky’.

““Reproductive labour is the familial and communitarian work that goes into sustain- ing and reproducing the worker.””

Women in Ireland

Through the lens of SRT, it becomes clear how the capitalist patriarchy subjugates every woman, every day. In an Irish context, the treatment of women has been a major sore point in the nation’s human rights record. There is often discussion on women’s rights brought up in outrage of extremity or violence - as evidenced by the heart-wrenching Mother and Baby homes, Magdalene Laundries, gender-based attacks and rates of domestic violence. However, these extreme occurrences did not emerge in a vacuum. The Irish state is not just complicit in sexism, it has misogyny built into the foundation of the nation. It is necessary to search for a path to women’s liberation even in the mundane, seemingly innocuous everyday. The passing of the 1937 Irish Constitution meant that horrifyingly strict gender roles were enshrined into law. Éamon de Valera’s almost exclusively male Fianna Fáil-led government endorsed Article 41.1, writing that the new State ‘recognises the Family as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society’ The Constitution was heavily influenced and partially drafted by the Archbishop of Dublin at the time, so although ‘Family’ was never explicitly defined, it is associated with the traditional gender roles promoted by the conservative patriarchal clergy.[8] The following article, which is still currently valid, reads

1° [...] the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.

2° The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.[9]

The article specifically codifies domestic labour as feminine work and identifies that the support or regeneration of the worker is essential for the functioning of the State. This limits a woman’s world to the walls that enclose her and establishes the family home as the workplace of reproductive labour; the foremost site where caring and regenerative activities occur. Women were legally encouraged and socially confined to domestic labour. The subsequent Marriage Bar (until 1973), forbidding married women from finding work in public service outside the home; the self-explanatory divorce (until 1996) and contraception (until 1980) bans; and of course, the 8th Amendment banning abortion further restricted the freedom of women, leaving them as quasi-prisoners in their own homes unable to make choices regarding their own autonomy and livelihood.[10] Across all classes, the socio-economic status of women left them often completely dependent on the waged labour of men. As late as the 1970s, the majority of women in Ireland were housewives.[11] While the situation has gradually improved since then, as women have fought to gain independence and sovereignty of the self, gender roles and presumptions about women engaging in reproductive labour remain.

““The Irish state is not just complicit in sexism, it has misogyny built into the foundation of the nation.””

In institutionalising marriage as the ‘fundamental unit group’ of society, the Constitution leaves Irish women with no support to pursue a life outside this model, as well as alienating and discriminating against those who do not fit into this vision. Furthermore, it is difficult to tell where the expectations of women stop and the identity of women begin. Federici writes, “Not only has housework been imposed on women, but it has been transformed into a natural attribute of our female physique and personality...Capital had to convince us that it is a natural, unavoidable, and even fulfIlling activity to make us accept our unwaged work.”[12] In turn, rebelling against this narrow life is not seen as the struggle of a revolutionary worker, but a failure, being unable to meet society’s idea of what a woman is. A valuable insight from SRT is that public life and private life are falsely separate. Both are sites of labour and exploitation under capitalism. This allows us to reimagine what work really is and extends our definition of ‘work’ to include reproductive labour, which despite being vital to the functioning of society has previously been overlooked. In the same vein, this offers opportunities for imaginative forms of resistance.

Communitarian Solutions

The Russian revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai conceptualised new, radical formations of family and community rooted in equality.[13] As the first woman in history to be a cabinet member, she used her position to advocate for women’s rights within the newly created Soviet state. Kollontai saw rearing children as a collective responsibility of society. Her abundant ideas included some of the demands fought for today: assistance to the family in the form of communal child care, public restaurants and food pantries, free education with school lunch included, equal pay for women workers, and family planning support, such as abortion rights and extended maternity leave. Kollontai strived to build a society in which ‘the indissoluble marriage based on the servitude of women is replaced by a free union of two equal members of the workers’ state who are united by love and mutual respect.’ Her writings on free love and women’s rights helped to inspire the creativity seen today in developing solutions to societal disenfranchisement through an SRT understanding.

Additionally, although it is still seen as the norm, the nuclear family blueprint is becoming increasingly difficult to reach for younger generations. Milestones such as owning a home and raising children now require two incomes to make a reality. Without adequate social support, women are forced to ‘pick up the second shift’ and engage in even more work. This plays into a growing ‘crisis of care’, only worsened by the onslaught of the pandemic.[14] Capitalist responses to these tensions in the archaic homemaker/breadwinner model are not viable long term solutions. They include the privatisation of caring provisions, or upper-class women outsourcing socially reproductive labour by hiring migrant women as cleaners and nannies. These attempted remedies only create more injustice. A sustainable path forward turns to the community and state to provide instead.

Ireland, like other capitalist states around the world, offers very little support for socially reproductive work, leaving it to fall mainly to women. By assuming some of these responsibilities and becoming aware of and ameliorating its own shortcomings in the communitarian sector, the state would lessen the burden on women and working class families. The social reproduction work of the community relates to an active civil society and includes proper housing, establishing open recreational spaces such as swimming pools, libraries, and gyms, as well as healthcare and medical services. The current Irish government struggles to provide, and does not prioritise, the socially reproductive work that should be under their jurisdiction. Proposed bills to insert rights to health and housing in the Constitution are struck down in the early stages of debating and voting in the Dáil. The current national housing crisis is well known. The infrastructure of public transport is of poor quality and expensive to use. Ireland is the only member of the European Union without universal healthcare - any reform moving toward this goal is stalled, with a large private market prioritised instead. Childcare services are also costly and inaccessible for many. There is a huge lack of development, especially in urban areas, for access to green spaces, playgrounds, and dynamic public parks. In allocating resources to fund spaces and services to regenerate the worker, the Irish state could improve the quality of life in its communities significantly.

““The nuclear family blueprint is becoming increasingly difficult to reach for younger generations.””

Another proposed initiative to elevate the status of women is the recognition of domestic labour through a universal basic income, which would also help alleviate the feminisation of poverty and uplift single mother households. Strengthening the welfare state would benefit all working women, offsetting the labour and time it takes to care for children and complete sisyphean household tasks. From the perspective of an SRT analysis, this would be a step in the right direction to achieving a more egalitarian nation.

Social Reproduction Theory in part explores the deeply connected relationship between capitalism and patriarchal values, in which individuals are not only being exploited as workers, but also oppressed as a result of their gender (further exacerbated, of course, by other compounding marginalisations). These identities, as we conceive of them today, were developed within and alongside the all-encompassing capitalist system and must be analysed as such, rather than as separate parts to a whole. In building a better and more equal society, we must be mindful and combat every aspect of this multifaceted situation, whether in or outside of the home.

Notes

Bhattacharya, Tithi, Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression (Pluto Press, 2017), p. 3.

Ibid.

Lenin, VI, ‘On International Women's Day’ Pravda, 4 March, 1920.

Bebel, August, Women and Socialism, Socialist Literature Co., 1879), ‘Introduction’.

Marx, Karl, Capital Volume I; Chapter 23 ‘On Reproduction’ 1867).

UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Women’ (UN Women Headquarters,2020).

Federici, Silvia, ‘Social Reproduction Theory: History, Issues and Present Challenges, Radical Philosophy.,Spring 2019.

Keogh, Dermot, ‘The Catholic Church and the Writing of the 1937 Constitution History Ireland, vol. 13, no. 3(2005).

Bunreacht Na HÉireann/Constitution of Ireland, 1945.

Laird, Heather, and Emma Penney. ‘The Issues with Ireland's “Women in the Home” Constitution Clause RTÉ, 8 March, 2021.

Bercholz, Maxime, and John FitzGerald. “Recent Trends in Female Labour Force Participation in Ireland,” Quarterly Economic Commentary: Special Articles, Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), 2016.

Federici, Silvia, ‘Wages for Housework’, All Work and No Pay, Power of Women Collective and the Falling Wall Press, 1975), p. 2.

Kollontai, Alexandra, ‘Communism and the Family’, Komunistka, No. 2, 1920.

Spear, Jess., ‘It Doesn’t Have to be this Way: Crisis in the Care Economy & the Role of the State’, Rupture No. 2, 2020.