The Exhausted Life

By Jess Spear

Ajay Singh Chaudhary, The Exhausted of the Earth: Politics in a Burning World (London, 2024).

In 1940, in the depths of the Second World War the German-Jewish philosopher, Walter Benjamin, wrote an essay criticising the socialist movement and vulgar Marxism. In his view, from the standpoint of fascism taking over Europe and the failure of socialists to stop this monstrous movement, the leading Marxists were missing an important aspect of how history is made in the here and now.

Benjamin penned eighteen theses and two addendums “On the Concept of History” which criticised those Marxists who viewed “revolution as a ‘natural’ or ‘inevitable’ outcome of economic and technical progress”.[1] In thesis number nine he wrote:

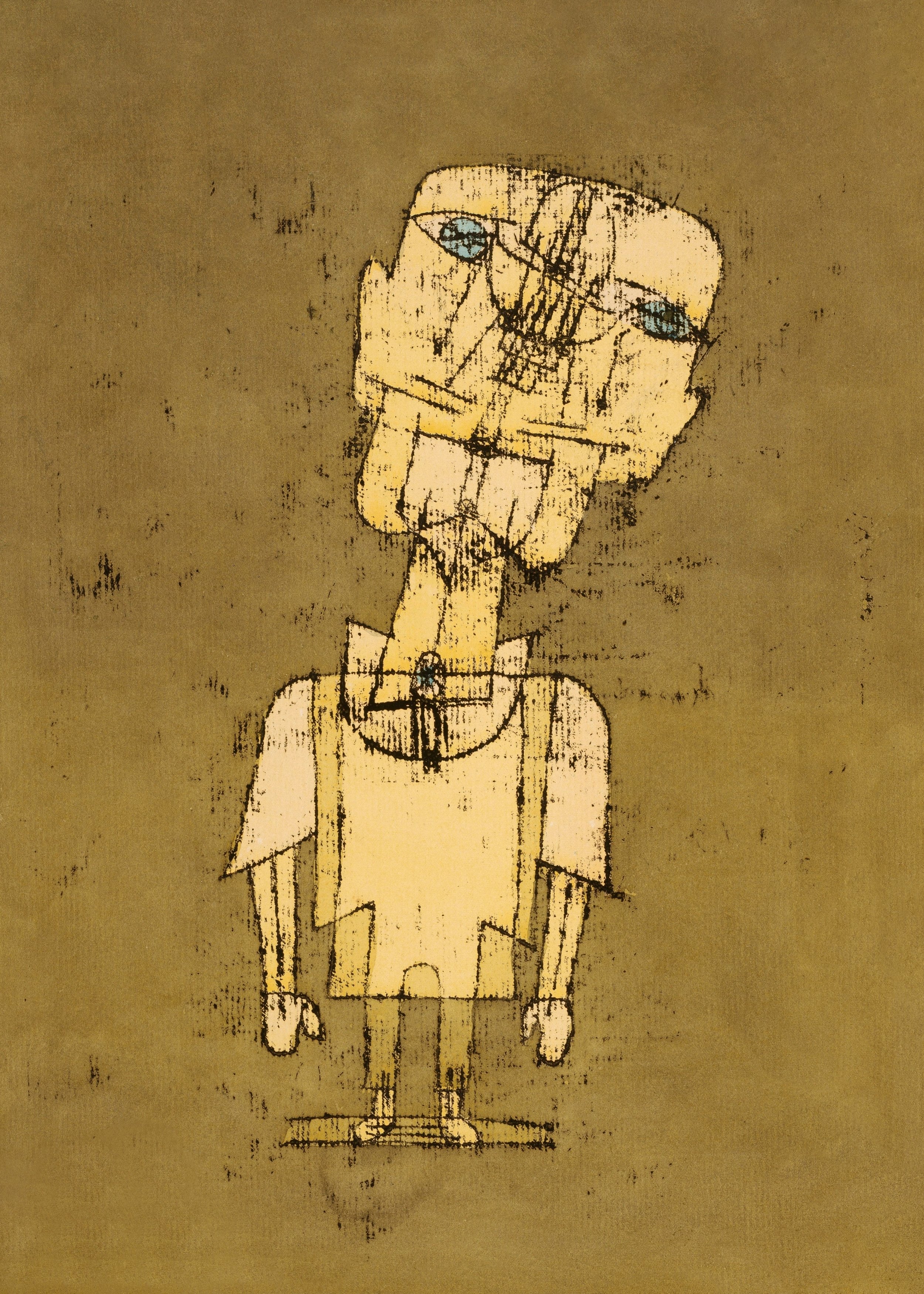

There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus [see below].

An angel is depicted there who looks as though he were about to distance himself from something which he is staring at. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth stands open and his wings are outstretched.

The Angel of History must look just so. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe - which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet.

He would like to stay, to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the rubble-heap before him grows sky-high. That which we call progress, is this storm.[2]

Angelus Novus by Paul Klee

When I read this a few years ago I thought I understood it. But it's really only in the last year that I can actually see what he’s talking about. “The single catastrophe” looks like a “chain of events” livestreamed to our phones: videos and images of extreme weather events, one after another, killer heat waves and deadly mass floods, and the genocide of the Palestinians. Unimaginable suffering in real time.

We can see the piles of rubble of this storm, of capitalism. The destroyed lives, deferred dreams, and forced trauma on generation after generation; the wars, land theft and enclosures, climate catastrophe, and extinction.

This catastrophe is not the future. It’s now. And with each passing day, the piles of rubble grow bigger.

But we should not forget that this progress is also a market filled with a thousand different squishmallows, an endless variety of things, but no access to healthcare or decent housing. It’s two-day shipping, but also the stress from an always-on capitalism that demands every second of our lives. It's the technology to have a child later in life, but no free time to be with them. It’s cheap meat and dairy but the land stripped bare and rivers choked by excess nitrogen.

It’s also the constant, never-ending advertisement telling me I’m not good enough. Or how nowadays nothing is built to last. It’s here today, broken tomorrow. This means you’ve to give over countless minutes, hours, and days of your life to look up what’s the best fucking toaster. It’s the mobile phone next to me that allows too many people to contact me on twenty different apps, at any time of the day. Or how about the horror you feel when you realise you forgot (or god forbid, lost!) your phone? (What might you miss?!)

The progress of this storm is above all, exhaustion.

The extractive circuit of capitalism

Since the dawn of capitalism and the making of truly world history, we in the “metropole”[3] have been linked to exploited peoples in the “periphery” through the extraction of raw materials in the (neo)colonies (for example, cotton picked by slaves in the American colonies and processed by workers in the cotton mills of England and Scotland). However, today’s capitalism is qualitatively different: “the machinery — the actual form and function — of twenty-first-century capitalism is an extractive circuit which quite literally crisscrosses the world”.[4] And “just as Marx once invited us to look behind the factory door,” in The Exhausted of the Earth: Politics for a Burning World Ajay Singh Chaudhary urges us “to ‘unbox’ the extractive circuit, catalogue its parts, and pry past a few bezels if we want to see Actually Existing Capitalism today.”[5]

Fully unboxing the extractive circuit would probably require multiple books, so Chaudhary uses the Philippines and the US to illustrate how capital has reshaped the working class and its conditions. For example, Filipino women migrating to the US find jobs covering relatively wealthy women’s second shift. The Filipino care worker isn’t there to give the California coder free time, but to allow them to work longer hours. Both are exhausted by the hyper-driven and lean production system.[6]

Of course, the California coder’s exhaustion is qualitatively different (and less) than the Filipino care worker forced to live in a different country to survive. Chaudhary isn’t trying to flatten out our experiences. He’s illuminating how global capitalism today “connects economically and ecologically dispossessed agricultural communities in the Global South with regimes of hyperwork in the Global North, rare earth ‘sacrifice zones’ with refugees, migrant labor with social reproduction, ocean acidification and atmospheric carbon with profitable opportunity.”[7]

The social media doom scrolling we’re all addicted to and the services many of us use to lessen our workload, like next-day grocery delivery, are part of the profit-making machinery of capitalism today. Chaudhary explains they are “shifting literal time and energy not to [us], but rather to the needs of an ‘always-on’ capitalism, creating the very crises to which these services respond.”[8]

In other words, we can’t get ahead. The extra time afforded by grocery delivery is taken back by the work emails you check in the meantime or the ad revenue you’re generating for social media. At the end of each day you feel spent, and in reality, you are.

More than that, this always-on, sped-up system is exhausting nature and human populations alike because “it’s not possible to achieve just-in-time production and delivery-on-demand...without burning through fossil fuels and human bodies mercilessly.”[9]

The capitalists, and the political establishment that serve their interests, are preparing for a world of climate chaos, a world in which billions suffer. After watching the horror of Gaza livestreamed to our phones, should we be surprised? Chaudhary reminds us that the “world as we know it already absorbs the scaling horrors of the Anthropocene.”[10] He points out that formal climate denialism isn’t really a thing anymore amongst the capitalist class - they no longer openly deny climate change in the same way they used to. Their response to the ecological catastrophe is what he calls “right-wing climate realism”. It’s investments in border patrols and security, retrofitting the military apparatus, and continuing to build and fortify “the extractive circuit”. That is, all the necessary policies to keep their profits flowing.

To counter this Chaudhary argues we need “left-wing climate realism” - a politics that acknowledges that the working class “make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”[11] We need a politics that soberly acknowledges the world we’re inheriting - climate chaos, gargantuan levels of pollution, extinction, and sea level rise to start - not one based on the techno-optimistic fantasies of the billionaire class.

“Nothing too shitty for the working class”

According to some left-wing ecomodernists, however, a planned economy is all that’s needed to resolve the ecological crises. There are no other planetary boundaries besides climate change.[12] Nothing much needs to change, and sure everyone wants and deserves the living standards of middle-class Americans[13,14]. Etcetera etcetera.[15]

There have been many well-considered responses to these arguments from degrowth scholars, Marxists, and ecosocialist activists. However, Chaudhary’s chapter, Climate Lysenkoism, is one of the most convincing and thoroughly enjoyable to read. He carefully dissects some of the more outlandish proposals like Small Modular Reactors and synthetic jet fuels and challenges the idea that people want more crap stuff. Who really wants more McDonald’s toys littering their homes or fifty-three different kinds of shampoo to choose from?

I would add: individual dishwashers and refrigerators for everyone[16] are not liberatory. We want community canteens (alongside other socialised household tasks) to liberate women, in particular, and everyone else from having to cook and clean individually. We want a completely different kind of life, not more of the same.

The minor paradise of the sustainable niche

In ecology “niche” refers to the specific role species play within the larger ecosystem. It denotes not only their dietary needs but their environmental range as well. Dung beetles, for example, have evolved to feast on different kinds of faeces, helping to process organic waste within an ecosystem. No dung, no dung beetle.

We humans have a niche too (obviously one that’s more variable than the dung beetle). Over the last 10,000 years, and greatly accelerated in the last 250 years, the human niche has expanded the world over, stamping out countless other species as new means for securing life’s necessities were developed and forcibly adopted. This destructive capitalist expansion threatens our life support systems[17] and, therefore, the future of human civilisation. What we need now, instead of the techno-optimism that ignores imperialism and planetary boundaries, is “to carve out a sustainable global human ecological niche capable of supporting the flourishing of some 7-9 billion humans.”[18]

But more than sustainable, the niche needs to be enticing and inviting. It should be something people desire. However, the “minor paradise of the sustainable niche” Chaudhary introduces isn’t about “another ‘bribe’ or ‘manipulation’ to garner popular enthusiasm.”[19] Rather, it’s to clarify that we want to create the conditions for everyone to live a good life, to live in a (minor) paradise. The “minor” underscores that this won't be a Garden of Eden per se, but that it “can be the overflowing abundance, rummaged from histories and imaginations, technologies and practices, with enabling constraints.”[20]

This isn’t eschewing technology. We need to utilise technologies requiring the least energy and fewest materials. Yes, we want public housing, but also beautiful spaces. The same goes for fashion and other historically developed needs and desires. But, above all, the minor paradise of the sustainable niche is “well within planetary boundaries and well within the structured necessity — the educated desire — for reversal, relief, and respite from exhaustion…” It would be “an ‘epoch of rest’.”[21] Sounds like heaven to me.

How do we get there? What power do we have to confront and defeat “right-wing climate realism”?

“The exhausted”

The answer for Chaudhary is “the exhausted” because “exhaustion guides us probabilistically to those who are already fighting and those who seem less bound, less attached to the world of business-as-usual.” The “exhausted of the earth” is a nod to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth[22]. Chaudhary references Fanon’s ideas throughout the book as he sees similarities in the “urgency” and “immediacy” of the decolonial struggle with the struggle to stop the extractive circuit.

Firstly because climate change demands an urgent and immediate response. As time ticks on, the question of halting the extractive circuit, of blowing up the pipeline, is posed more and more sharply. But, also, and importantly, the further development of the extractive circuit will spread an “affectivity” or feeling of exhaustion amongst wider layers of people. It will spread “colonial relations” - police repression, violence, and “the growing mass of surplus population” - into the “metropole”, bringing more and more people into conflict with the state. These conditions help to fuse a “stretched class composed not uniformly in relation to production, but in disparate social blocs… arrayed along the extractive circuit, in capitalism’s long supply chains, and in those people and places consigned, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore writes, to ‘organized abandonment’.”[23]

I agree with Chaudhary that “class struggle occurs across a range of terrains, not simply or even centrally the workplace.” Any proposal that we limit our focus to direct wage earners, or even wage earners in particular professions, usually male-dominated, would be theoretically and practically disarming. (Particularly considering there are relatively few industrial workplaces here in Ireland.)

The biggest social movement in Ireland in the last decade was the anti-water charges movement. It was undoubtedly a class struggle, but it was not a “workplace issue” and it was certainly not led by industrial workers. Working-class women, many of them stay-at-home mothers, refusing the installation of water metres and organising their communities, were leaders in a mass movement of non-payment and street protests that won.

This offers an important insight into how working-class struggle actually takes place in many deindustrialised, wealthy countries today. At the same time, the power of the working class is generally greatest at the point of production. Both of these understandings can co-exist and inform our work. We can’t and shouldn’t wait for industrial workers (or other unionised workers) to go on strike. Chaudhary is right that we have “to build from existing formations and from a broader global majority (in both North and South) that is most likely to reject the world of exhaustion…”[24] That means an orientation to working-class struggle wherever it breaks out in opposition to this system.

Perhaps strikes will feature less than street blockades, which Chaudhary points out also have the power to halt the extractive circuit and defeat governments, but I’m not convinced. I think we have to be open to “any means necessary” while simultaneously pressuring the trade unions to join the fight.

It’s also not just about who is willing to fight against this system, but what will they be fighting for? What is their end goal? Are you fighting for your own plot of land or collective farming? Different sections of exhausted people will desire different outcomes. In the united fronts and coalitions we build to confront capital, in the “stretched class” of the exhausted, whose interest does the ecosocialist represent?

For revolutionary Marxists (like me), the answer is ‘the working class’. Our ultimate aim is to abolish private property and establish common ownership and democratic planning, to lay the material foundations for “from each according to their abilities to each according to their needs”. Not everyone willing to fight the system, who join hands with us in the fight, here and now, will agree with that.

That doesn’t mean your politics should only speak to the working class. The demand for “peace, land, and bread” popularised by the Bolsheviks summed up the desires of workers and peasants in Russia 1917, cementing a worker-led alliance that not only won a revolution but successfully defended it. The challenge is to knit this recognition and commitment to broad working-class struggle, often taking place outside the workplace and within wider coalitions, together with working-class power.

Chaudhary’s concept of “exhaustion” has the potential to help unite a broad coalition and promote the general interests of the global working class. However, an ecosocialist strategy must not only identify and work to unite the exhausted, but seek to wield the power available to us, to strike blows against and ultimately defeat the capitalist system.

The politics of exhaustion

What stirs people to action is not bread and butter “issues”: it’s not wages, it’s how people feel about those things. This is why the “culture war” works for the establishment. “It is not only wealth and power that runs through the extractive circuit”, Chaudhary explains, “feelings flow through it as well.”[25] Richard Seymour’s book Disaster Nationalism makes a similar point, “We are passionate animals. Passion, as Karl Marx wrote, is our ‘essential force’.[26]

Of course, socialists should illuminate the objective reality people face that engender feelings of resentment and a sense that things are unjust - the bullshit jobs, the lack of dignity, or no access to therapies for your children with additional needs. But, where is the space on the left for people to express their feelings of resentment, anger, and passion? Protests? Yes, but too many protests that lead nowhere mean people stop coming and lose hope. What else do we offer? How do we help transform “momentary passions” into “coordinated political action”?[27]

The politics of exhaustion starts with recognising how fast the world is changing and the impacts on working-class and oppressed people: the fraying social fabric, the sped-up, always-on system demanding so much of our attention, and information overload in addition to inadequate public services and housing. Not to mention the changes in young people’s relationships and sex lives.

It means we draw attention to the aspects of our programme that address the exhaustion so many people are feeling - demands for free time and rest. Physical rest like a four-day work week, community canteens and laundromats, longer mandatory holidays, and more public holidays. But also, mental rest. We should be demanding public space is scrubbed of advertisement, which “pollutes the mental, just like the urban and rural, landscape; it stuffs the skull like it stuffs the mailbox.”[28] Why should we be bombarded with ads as we walk down the street?

This is something the leader of La France Insoumise, Jean-Luc Melenchon, does very well.[29] In the most recent French parliamentary elections, he put forward a bold vision “to harmonise the rhythms of production with those of nature…to nationalise time” because “we say the time of life, the time which counts, isn’t only the time you believe useful because it's producing, time isn’t only the time under constraint, useful to society, time spent working, it's also free time…where we ourselves decide what we’ll do…to live, to love, to do nothing, to attend to our loved ones, to read poetry, to paint, to sing…Free time is the time when we have the possibility to be fully human, that’s what we’re talking about.”[30]

A politics of exhaustion should also address the deep feelings of hatred for the class enemy. It should acknowledge the long-awaited justice so many people want for their loved ones. “Where is the anger or disgust with contemporary conditions?”[31] Chaudhary asks.

Walter Benjamin wrote that “social democracy contented itself with assigning the working-class the role of the savior of future generations. It thereby severed the sinews of its greatest power. Through this schooling the class forgot its hate as much as its spirit of sacrifice. For both nourish themselves on the picture of enslaved forebears, not on the ideal of the emancipated heirs.”[32]

Our struggle is not for future generations, it is for ourselves and for all those we see suffering now, who have been killed and maimed, and who aim for dignity in the present. We need a politics of now, which confronts a constantly accelerating capitalism hell-bent on maintaining profits at any cost and assembles the forces necessary for its destruction. The Exhausted of the Earth is essential reading for activists tired of this life, who dream of an ecosocialist world (where they can finally rest) and are eager to discover new analyses and concepts to prepare for the coming battles.

Notes

Michael Lowy, Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s "On the Concept of History" (London, 2005).

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”, Marxists.org

The metropole is akin to “Global North” in that it refers to countries that dominate “less developed” countries that are “dependent”.

Ajay Singh Chaudhary, The Exhausted of the Earth: Politics for a Burning World, (2024, p61.

Ibid p62

For a good overview of lean capitalism and just-in-time production see Kim Moody’s On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War (2017).

The Exhausted of the Earth, p61

Ibid p76

Ibid p78

Ibid p54

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marxists.org

Matt Huber, “The Problem With Degrowth”, Jacobin, 16 July 2023.

https://x.com/Leigh_Phillips/status/807476612987961344

https://x.com/Leigh_Phillips/status/1614307941859086336

For a more detailed description, I recommend Kai Heron’s article, “Forget Ecomodernism”, Rupture.ie, 8 April 2024.

https://x.com/Leigh_Phillips/status/1836807769833517282

We have now surpassed 6 of the 9 identified planetary boundaries which denote the necessary conditions for humanity to survive. See here: https://www.pik-potsdam.de/en/news/latest-news/earth-exceed-safe-limits-first-planetary-health-check-issues-red-alert

The Exhausted of the Earth, p163

Ibid p126

Ibid p169

Ibid p186

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York, 2004). This was originally written in 1961, but Chaudhary is citing from this edition.

The Exhausted of the Earth, p219

Ibid p144

Ibid p210

Richard Seymour, Disaster Nationalism: The Downfall of Liberal Civilization (London 2024).

The Exhausted of the Earth, p266

Michael Löwy, “Advertising Is a “Serious Health Threat”—to the Environment”, Monthly Review, 1 January 2010.

David Broder, “Jean-Luc Mélenchon Is Popular Because He Confronts the Powerful”, Jacobin, 18 June 2022.

https://x.com/broderly/status/1641910171914891264

The Exhausted of the Earth, p155

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”, Marxists.org